Fighting for ground in the public imagination

This post is adapted from a talk I gave at the University of Victoria on October 21, 2019 as the Honorary Resident Wikipedian. Special thanks to my hosts Lisa Goddard, Alyssa Arbuckle, and Ray Siemens for creating a stimulating and welcoming environment to discuss and further causes related to open and democratic forms of knowledge production.

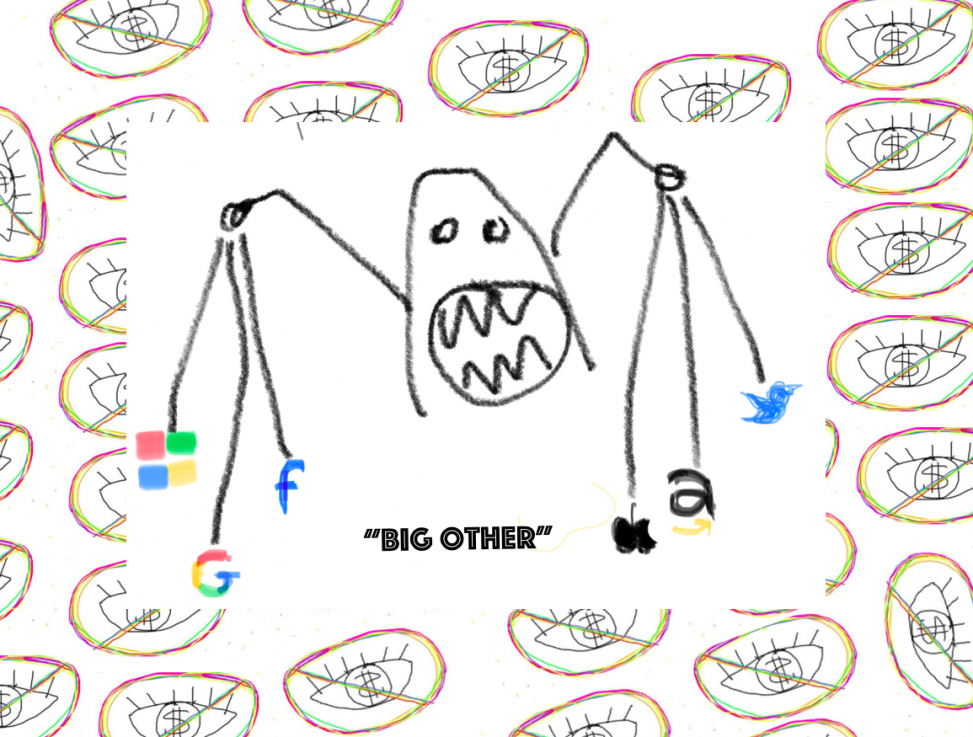

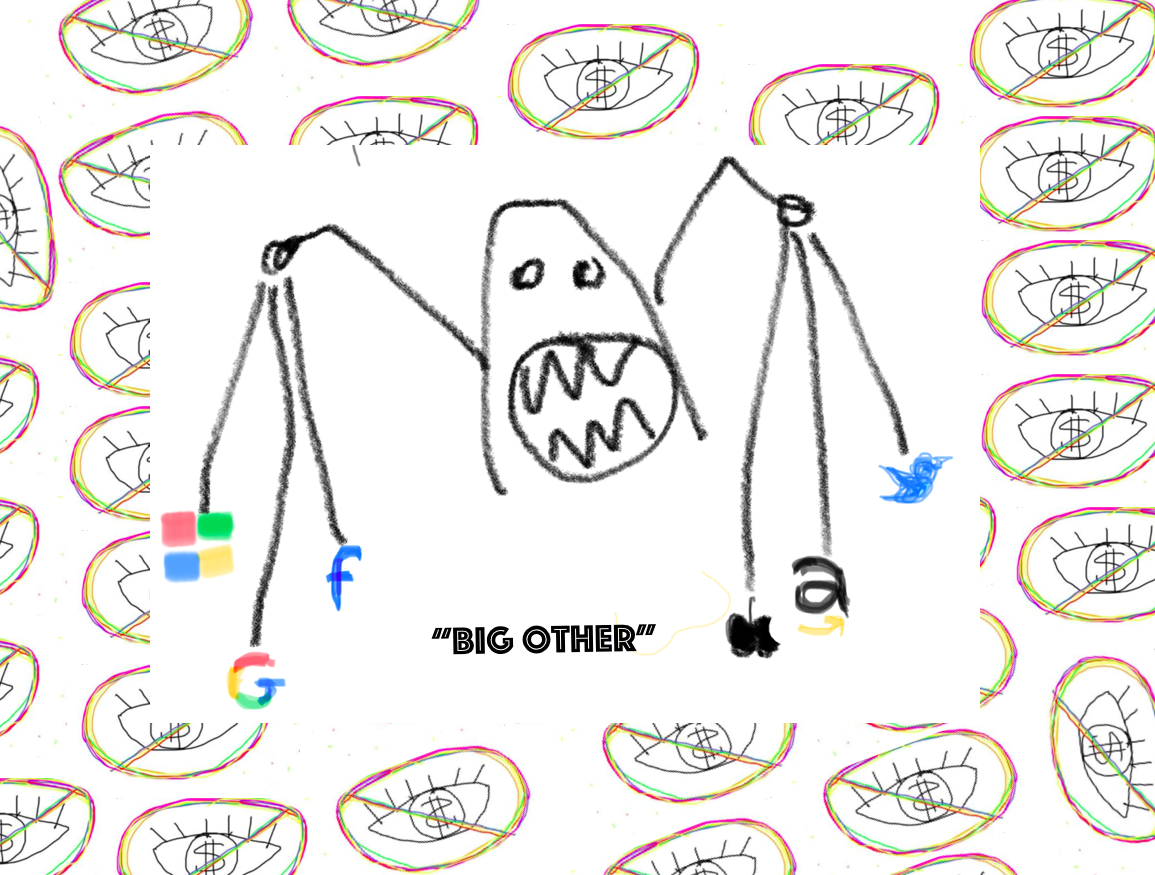

readers are invited to doodle along as part of the imaginative process of resistance

Open access has a surveillance problem.

No, I don’t mean to suggest that open access is necessarily surveillant, or that it is aiding and abetting the digital surveillance industrial complex—although it certainly can.

The problem is much worse.

The trends of surveillance and control in the broader information landscape not only will likely affect the strategies and effects of open access in the future, they also speak to the limits of an apolitical conception of knowledge itself.

In the spirit of this year’s open access theme “Open for Whom?,” I want to ask us to think about how deepening our imagination about the purpose of knowledge may help us productively respond to the growing and seemingly unstoppable prevalence of surveillance and control in our academic and popular digital technologies

Is open access about the free distribution of knowledge for its own sake? Or is it about empowering people to collectively transform the world?

Without deepening the vision of open access for our age of surveillance technology, we run the risk of gaining openness at the expense of freedom. We also lose out on one of the most promising opportunities to help the general public resist and transform surveillance technology into technology for the common good.

Let me explain.

Surveillance capitalism

For those of you familiar with the concept, or even critical of the book that recently popularized it, hang on a minute.

For those of you who aren’t, let me quickly introduce you. Last January, the business scholar Shoshana Zuboff published the book The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for the Future at the New Frontier of Human Freedom, which offers a critique of our digital status quo via the underlying economic logic that supports it.

Zuboff names this new economic logic “surveillance capitalism,” which she argues (more succinctly in an earlier article) aims to “predict and modify human behavior as a means to produce revenue and market control” (2015 75). According to Zuboff, nearly every aspect of human activity is on its way to becoming monitored and controlled by intelligent devices as part of an elite hyper-capitalist minority’s quest for profit. As a consequence, democracy, individual freedoms, and what she calls the “right to the future tense” are being sacrificed as powerful digital corporations work towards the mass engineering human society. In short, the problem with surveillance capitalism is not merely that we are being surveilled, it’s that we are being manipulated and controlled.

Identifying “control” in surveillance technology

These claims about control, you might think, are somewhat overblown. But the book documents, quite persuasively, the many ways that human behavior is now routinely monitored, analyzed, predicted, and nudged at scale by some of our most popular digital technologies. Zuboff extensively quotes senior level executives, software engineers, and researchers confirming that control is in fact the ultimate aim of their products. As one software engineer says in an interview:

The goal of everything we do is to change people’s actual behavior at scale. We want to figure out the construction of changing a person’s behavior, and then we want to change how lots of people are making their day-to-day decisions” (2019, 297).

Or here’s another interview excerpt:

The new power is action. [. . .] It’s no longer simply about ubiquitous computing. Now the real aim is ubiquitous intervention, action, and control. The real power is that you can modify real-time actions in the real world. Connected smart sensors can register and analyze any kind of behavior and then can actually figure out how to change it. Real-time analytics translate into real time action”(293 ).

But of course, we don’t really need to rely on Zuboff to give examples of this control. We see tech companies carry out control in other powerful ways all the time.

For example, tech companies control the design and policies of major communication platforms, often in ways that prioritizes clicks and engagement over factual, ethical, and community-governed communication, corroding public discourse and public understanding.

Tech companies also carry out control through blackboxing their code, prohibiting users or public oversight groups from understanding and modifying software processes that monitors and influences many of users everyday activities and communications. This lack of access leaves user communities powerless to understand the way companies might be using personal devices against users’ interests.

We see tech companies exert control in their secrecy or dishonesty about their collection and instrumentalization of user data, leaving users in the dark as to how their data is being used by corporate and governmental entities.</p>

<p>And there are many other examples. One of the problems, however, is that even if we theoretically know about these forms of surveillance and control, it can still be difficult to imagine their significance as we go about using our many digital devices and services.

This is where metaphors can come in handy. They stimulate our imagination in ways that can help enhance our awareness and concern and begin to imagine alternatives. The reason I want to talk about Zuboff today, is that she offers us one such metaphor that can help us begin this imaginative process.

The metaphor she offers is “Big Other.”

Big Other

Zuboff defines “Big Other,” as “the sensate, computational, connected puppet that renders, monitors, computers, and modifies human behavior” (X). The goal of this puppet is to extract what she calls “shadow text” from our digitally-surveilled behavior to feed its puppet master Surveillance Capitalism. Though we produce the “shadow text,” we never see it. It is “read only” for the surveillance capitalists (186). And the shadow text enables what she calls the “asymmetry of learning” where only surveillance capitalists are able to analyze and instrumentalize the population’s behavioral and communicative data.

I like Zuboff’s metaphor of Big Other because it invites us to see our phones, our computers, our email platforms, our search engines, and so forth, not simply as useful tools that enable us to collaborate and communicate, but as the eyes, ears, hands, and brains of a creature that is using us for its own interests. Each time that we engage with these tools, we are not simply getting our own intended use out of it, but we are also feeding Big Other “shadow text” which helps it grow the strength and influence of its own bodies and brains. We are helping, in other words, Big Other grow more resistant against our attempts to change it.

I also like the metaphor of Big Other because I think it retains its value across ideological viewpoints. While Zuboff describes Big Other as a “new species” of technological power, Evgeny Morozov argues that its processes of surveillance and control are in fact simply an extension of the inherent logic of capitalism. In other words, they critique Zuboff for putting too much blame on technology, rather than capitalism itself. This is an important point and merits further discussion. But whether you believe Big Other is a symptom of technology or capitalism, both viewpoints are compatible with this metaphor of an alien figure hiding in our midst and absorbing our agency.

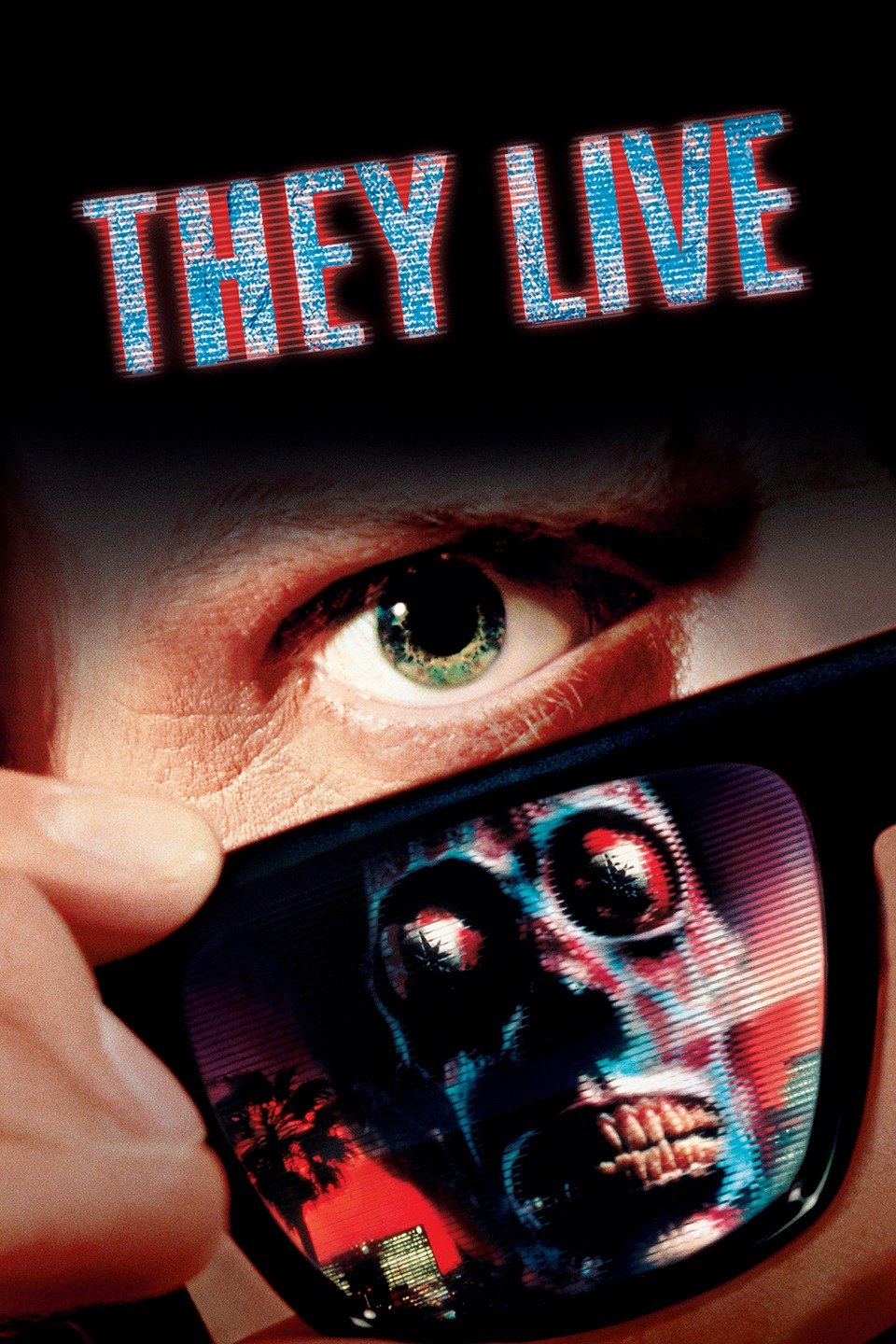

It’s a metaphor that lends itself to connecting with other metaphorical representations of surveillance and control in society. We might see, for example, a relative of Big Other in John Carpenter’s 1988 film “They Live,” where a secret alien ruling class controls humans by embedding subconscious commands to obey and consume in their popular media. A drifter named Nada comes across a pair of glasses that allows him to suddenly see the way the population is being controlled by these messages for the benefit of this alien ruling class. Nada spends the rest of the film concocting a plan to reveal this hidden reality to humans. The alien power relies on human ignorance of their power, so thought is, once humans know about it, they’ll be able to take back their power from the aliens.

It’s a metaphor that lends itself to connecting with other metaphorical representations of surveillance and control in society. We might see, for example, a relative of Big Other in John Carpenter’s 1988 film “They Live,” where a secret alien ruling class controls humans by embedding subconscious commands to obey and consume in their popular media. A drifter named Nada comes across a pair of glasses that allows him to suddenly see the way the population is being controlled by these messages for the benefit of this alien ruling class. Nada spends the rest of the film concocting a plan to reveal this hidden reality to humans. The alien power relies on human ignorance of their power, so thought is, once humans know about it, they’ll be able to take back their power from the aliens.

It seems like a reasonable plan. And in fact, it shares much of the same logic as our own critical research on technology. If humankind finally sees the presence of Big Other lurking in our devices, then Big Other’s power over us should begin to vanish. Like the power of the secret alien ruling class, the power of Big Other relies on a compliance we could quickly refuse..

So that’s the question. Would broad knowledge of Big Other be enough to take away its power?

Now that we’ve all seen it, will we right now stop using its tools?

It’s a good question.

Failure of tech criticism?

Zuboff’s book, as you may know, received a great deal of mostly favorable attention in high profile media outlets like The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and The Guardian, its key ideas have permeated across online discourse from the Twittersphere to a Zadie Smith essay defending literature, it has even inspired some high level tech figures to publicly critique Big Tech practices. And yet still, surveillance capitalism seems as powerful as ever before.

And perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised.

Because Zuboff is hardly the first to point out the exploitative techniques of dominant digital technology practices. Just think of Tiziana Terranova’s excellent research article “Free Labor: Producing Culture for the Digital Economy,” published nearly twenty years ago. There is also, of course, Jodi Dean, Nick Srinick, Christina Fuchs, Dal Yong Jin, and many, many others.

We put on these glasses. We agree there is an alien in our midst. And yet we fail to act.

This is a failure that I think Rob Horning was observing when he declared last month that “tech criticism has basically failed.”

He writes:

Despite the steady flow of complaints in more and more high-profile media outlets about “surveillance capitalism” in its many guises — the way it erodes privacy, abolishes trust, extends bias, foments anxiety and invidious competition, precludes solidarity and resistance, exploits cognitive weaknesses, turns leisure into labor, renders people into data sets or objects to be statistically manipulated, institutes control through algorithms and feedback loops, and consolidates wealth into the hands of a small group of investors and venture capitalists with increasingly √reactionary and nihilistic politics — many people are still going to go with the flow and get the latest gadgets, because why not?

I think there’s actually an interesting lesson in this observation.

“Despite the steady flow of complaints [. . . ] many people are still going to go with the flow [. . . ]”

In other words, despite the tremendous amount of knowledge and general agreement about the toxicity of our digital status quo, we seem powerless to change it.

Despite knowing what’s wrong, we don’t actually know how to change it.

Why is that? Are the critics of digital technology in fact wrong? Are their concerns overblown? Does no one actually believe them?

Or, is there in fact something like what Horning calls “the flow” that is much more powerful than knowledge alone?

What is this flow? And why is it so powerful?

The Flow

The flow is something we probably encounter all the time in our everyday choices, and certainly not just in relation to digital technology. Maybe you believe cars and air travel are environmentally toxic, but you use them frequently because your city, job, and social life are dependent on them. Or maybe you have concerns about the labor practices of factories that produce consumer goods, but you don’t create a supply chain research project every time you buy a pair of socks. And, back to our particular theme, maybe you’re concerned about the practices of major digital technology companies, but you still use their tools because finding and setting up alternatives would take more time and expertise than you have.

As the journalist Kashmir Hill reported, it is nearly impossible to avoid these companies, even if you make it a full time job to do so.

Hill spent five weeks untethering herself from Amazon, Facebook, Google, Apple, and Microsoft. The process required an enormous investment of time, outside expertise, expenses, and was ultimately still impossible. She writes,

Critics of the big tech companies are often told, “If you don’t like the company, don’t use its products.” I did this experiment to find out if that is possible, and I found out that it’s not—with the exception of Apple. These companies are unavoidable because they control internet infrastructure, online commerce, and information flows. Many of them specialize in tracking you around the web, whether you use their products or not. . . . These companies look a lot like modern monopolies.

Besides, what would your individual opting out matter when these companies count their users by the billions?

This technological monopoly, the practical difficulty of resisting it, the belief that your individual resistance hardly matters . . . this is all part of the flow.

And it is mighty.

In the face of the flow, of trying to speak out against the flow, I think it can be quite easy to develop a Cassandra complex, or the belief that you alone, or you and a few knowing friends and colleagues, are aware of the true political stakes of digital technology.

Cassandra, if you remember, is a tragic figure from Greek mythology, who had been given the gift of prophecy by the god Apollo as part of his attempt to woo her. Cassandra, however, rejected Apollo’s advances, and so he followed up his gift with a curse: that no one would ever believe her.

That curse ended up being quite tragic, both for the city of Troy, which suffered through ten years of catastrophic war before its final destruction, and for Cassandra, who was dismissed as a madwoman before being raped and kidnapped at her city’s end.

Though she knew with the accuracy and certainty of the gods which events would lead to the brutal ten year war and the destruction of Troy, her knowledge was utterly powerless. Not because she was wrong. Not even because—we have to assume—she did a bad job communicating it. It was divinely ordered to be so.

Knowledge about the exploitative practices of Big Tech is freely and publicly exchanged everyday. In a certain sense, this genre of public discourse is an exemplary model of “open access,” sharing the fruits of its critical research far and wide. And yet, ironically, much of this sharing happens through Big Other; in effect, our critique of Big Other adds to its strength. In fact, the processes of making and sharing this knowledge are in contradiction with the aim of sharing the knowledge in the first place.

Like Cassandra, we might know that Big Tech’s practices are working towards the end of the democratic project or our world as we know it. And yet, despite this free, public knowledge, we seem powerless to stop it.

Open Access

The free, public exchange of knowledge, scientific and academic knowledge in particular, is precisely the aim of the open access movement. It is a noble goal, and given advances in computing technology and its availability, it is a more realistic goal than ever before. However, as the movement continues to grow, I think the open access movement should be looking very carefully at the way information is being managed, instrumentalized, shaped, and monetized in the broader information landscape. Because academic knowledge of course, is a species of information, and thus it will be subject to the same pressures and instrumentalization

We should ask ourselves if the presence of Big Other in our information landscape—from the classroom to the public sphere—has any bearing on the mission, strategies, or effects of the open access movement

At first glance, we might think it does not. Historically speaking, the open access movement’s core struggle has been to free academic knowledge production from restrictive copyrights enforced by academic publishers, not surveillance capitalist firms, which have only emerged recently.

If anything, you might say, surveillance capitalism has helped the open access movement in its provision of freely-available digital tools to share knowledge and promote the open access movement. In fact, in some ways, open access and surveillance capitalism seem to share a kindred mission. For example, Google’s mission is to “to organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful.” So even if we agree that surveillance capitalism isn’t the most ethical mode of developing and deploying digital technology, we might not see it as actually interfering with the interests of the open access movement.

That’s one way to look at it.

But I want to offer another perspective. I want to invite us to put on our magical glasses that allow us to detect the presence of Big Other. This time, however, I want us to use them to take a look at the institution that is the home of the open access movement, that is higher education. Where is Big Other here? Where do we find surveillance and control? Does it matter?

Big Other on campus

First, we will of course find Big Other lurking in most of the cell phones, laptops, and other personal devices carried by students, faculty, and staff. But we will also likely find the presence of Big Other in a majority of the networked computers in public computer labs, in the administrative business systems, in the educational content management systems and plagiarism checkers, in the Microsoft, Google, and Amazon ‘powered’ email and cloud services, and in the host of other digital tools used to carry out the day-to-day activities of academic life. In fact, Big Other is so ubiquitous it will likely be difficult to find a part of the university that is protected from its reach.

First, we will of course find Big Other lurking in most of the cell phones, laptops, and other personal devices carried by students, faculty, and staff. But we will also likely find the presence of Big Other in a majority of the networked computers in public computer labs, in the administrative business systems, in the educational content management systems and plagiarism checkers, in the Microsoft, Google, and Amazon ‘powered’ email and cloud services, and in the host of other digital tools used to carry out the day-to-day activities of academic life. In fact, Big Other is so ubiquitous it will likely be difficult to find a part of the university that is protected from its reach.

Higher education, it turns out, is a wonderful environment for Big Other to thrive. We generate shadow text in abundance!

Big Other’s robust presence on campus marks what Ben Williamson calls the “platform university,” where “students are raw material for monetization.”

But this monetization isn’t limited to students. It’s encroaching upon all of the university’s processes.

In the 2019 SPARC Landscape Analysis, Claudio Aspesi and others observe that a “set of companies is moving aggressively to capitalize on [university data]” and that the consequences are concerning:

Through the seamless provision of these services [such as learning management systems, workflow tools, assessment systems], these companies can invisibly and strategically influence, and perhaps exert control, over key university decisions – ranging from student assessment to research integrity to financial planning. Data about students, faculty, research outputs, institutional productivity, and more has, potentially, enormous competitive value. It represents a potential multi-billion-dollar market (perhaps multi-trillion, when the value of intellectual property is factored in), but its capture and use could significantly reduce institutions’ and scholars’ rights to their data and related intellectual property.

And the value of university data is becoming increasingly clear. We can get a sense of it, for example when companies like the plagiarism checker Turnitin are sold for $1.75 billion to media companies who have no other history of educational investment. Or when major academic publishers like Elsevier rebrand as an “information and analytics” company.

Big Other, I’d like to suggest, is not just present on the university campus, it is in fact the new central subject of the university, gaining more power everyday to shape, control, and monetize university processes. It is both the new student and the new researcher, in that it is learning from the massive amount of behavioral surplus it gathers and analyzes from higher education, and it is formulating and testing an unthinkably wide array of hypotheses concerning its subject-matter: us.

This learning, however, is not for the common good, it aligns with what Zuboff describes as the asymmetrical division of learning, where the gathering, analysis, and implementation of knowledge about the many is done in secret for the elite few.

And Big Other is also, in many ways the new teacher, teaching academic populations to passively accept its presence as natural, neutral, and inevitable.

But aren’t the tools of Big Other, we might wonder, just making learning and research more efficient and effective?

That depends, I think, on what you think the purpose of research and learning are.

Knowledge for agency

Academic knowledge making practices, since the birth of the modern university in the late 19th century, have largely aspired to an objective ideal, employing writing as a medium for making neutral, universally-valid, archivable, and permanent forms of knowledge, or what they called “brick(s) in the temple of wisdom” (Russell 71-72). In this conception, knowledge is understood largely as a set of objective, documentable facts to be discovered, shared, taught, and learned. Academic libraries and publishers grew up around supporting the archiving and dissemination of this conception of knowledge. And digital technology, as the open access movement recognized, could in theory open up these processes of sharing knowledge to broader publics than ever before.

There is much value in this conception of knowledge, and the types of knowledge making processes and uses it enables. But it is only one particular way that we might imagine and understand what knowledge is, how it works, what it requires, and what it should do.

Or you might say, it is only a partial understanding.

Paulo Freire, one of the founding thinkers of critical pedagogy, is one theorist who might help us consider knowledge as being much more than simply objective facts to be discovered, transmitted, and archived.

For Freire, knowledge is part of a process in which a people collectively work towards critically understanding and transforming their world. The sharing of objectively-held facts is an important part of that process, but it is certainly not the final goal. Because ironically, the sharing of objectively held facts can in fact work towards the suppression of critically understanding and transforming the world. And this suppression, far from being knowledge making, is how Freire defines oppression.

In his book Pedagogy of the Oppressed, Freire documents the many surprising ways that sharing objectively-held facts can in fact teach people to think they are powerless, incapable of thinking or acting for their own needs and interests. They learn to passively accept an image of the world that has been shaped according to the interests and ideology of a dominating class.

Freire was writing about education, but I think his point also applies to the broader information landscape. Surveillance capitalism has shown us that the free exchange of knowledge can in fact be co-opted as a means to monitor and control populations—in other words, as a means to oppress. Because surveillance capitalism—in its facilitation of the free exchange of knowledge—denies critical understanding and agency in numerous ways. It denies users and the broader public the right to critically understand how its code works, how user data is instrumentalized, or how algorithmic design manipulates public discourse. Surveillance capitalism also denies users and the broader public the right to change these policies and these systems according to public interests. From a Freirian perspective, despite their great capacity for sharing knowledge, the technologies of surveillance capitalism are oppressive. They fill us with immense but powerless knowledge, they makes Cassandras of us all.

Those of us that are interested in the open access movement should consider this. Do we care about the access of facts for their own sake, or are we working towards a vision of open knowledge where facts are part of a process of empowering people to critically understand and transform?

Can we imagine what a Freirian commitment to open access might mean? Can we imagine why it would matter and what it might look like?

Imagining Big Us

I’ve been thinking a lot lately about the role of the imagination in regards to these issues. Even though we can put on our critical glasses and see what might be wrong with the status quo of our information technology systems, it can be very hard to imagine what we might do instead and why it might be meaningful. Without imagined alternatives, it’s also nearly impossible to communicate to others why we should be working towards another model.

The imagination and its creative products are of course essential in growing a strong and influential movement. As Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri argue, “Not only can art expose the norms and hierarchies of the existing social order, but it can give us the conceptual means to invent another, making what had once seemed utterly impossible entirely realistic” (Hardt & Negri, 2009).

The environmental movement offers one example of how the imagination is vital for launching and growing social movements. In a study on climate change activism and science fiction, Shelley Streeby argues that imaginative forms of storytelling were foundational for moving “large numbers of people to act and imagine alternatives to the greenhouse fossil fuel world” (14) at the movement’s beginning in the 1960s. In particular, Streeby credits the scientist Rachel Carson’s book Silent Spring — which employed imaginative storytelling techniques — as a catalyst to the formation of the Environmental Defense Fund in 1967. The Environmental Defense Fund brought environmental lawsuits against the state, resulting in new state policies and institutions such as the National Environmental Policy Act and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Today, while the struggles of the environmental movement have only seemed to grow, its issues have at least penetrated popular consciousness, where they have opportunity to instigate action and debate. Everyday, we encounter the recognizable figures from the environmental movement (like Greta Thunberg), proposed legislation (like the Green New Deal), and countless products and services that are responding in some way to its issues, such as electric cars, curbside recycling, compostable bags, and so forth. Even if you don’t agree with these figures, policies, products, or services, they at least signal a popular sense of responsibility and a capacity to act. They are a testament to the belief that we can in fact choose to make the world differently than it appears now. And the imagination, as Streeby demonstrates, played a powerful role in popularizing and empowering the movement.

As Walidah Imarisha argues in the introduction to an anthology of science fiction inspired by the work of Octavia Butler, “the decolonization of the imagination is the most dangerous and subversive form there is.” Imarisha describes fiction that embodies this decolonization as “visionary fiction,” or a type of science fiction “that has relevance towards building newer, freer worlds” rather than reinforcing “dominant narratives of power” (4).

What I want to ask us today then, is where are the visionary cultural works that can help us push back against Big Tech and build a freer technological world? Where are the films, poems, novels, and songs that can help us imagine another way of digitally acting and connecting?

Broadly speaking, our technological imagination has seemed largely dominated by the current culture of computing. Whether celebratory, satiric, or dystopic, we see the same myths about digital technology repeated in television, film, and literature over and over: that digital technology is something made by experts far away as part of a highly-competitive, cut throat industry that values profit over the common good. Even when works exhibit a clear criticism for the digital status quo, such as Silicon Valley or Mister Robot, there is very little representation of alternatives beyond the false dichotomy of corporate tech or anarchic hacker. Rarely, do we hear about the broad range of computing projects, communities, and movements that have theorized, advocated, and have even sustained approaches to digital technology that embody entirely different values, such as user freedom and user privacy, public oversight, democracy, equity, and peace. We don’t have popular cultural works that examine the histories of these alternatives or dream up their future possibilities, thereby suppressing their presence in popular consciousness.

But these alternatives did or do in fact exist. Think of Computer People for Peace, the Free Software Foundation, participatory design IT initiatives, the Tech Workers Coalition, Minitel, Plato, and so forth. None of these organizations or projects were or are necessarily perfect, but they point to models where technology might be driven less by Big Other, and more by the users that use them. Us.

We don’t see these alternatives represented in popular culture and we also don’t see them represented in higher education. When I talk to students, for example, I find that their imagination about what digital technology is and can be, is often profoundly shaped by the practices of the dominant digital technology companies of the day—that is Google, Facebook, Amazon, Apple, and Microsoft, and the surveillant culture of computing which those companies actively shape. As Chris Gilliard writes, “Web2.0—the web of platforms, personalization, clickbait, and filter bubbles—is the only web most students know.” Whether they celebrate or condemn the practices of these companies, many students express a sort of passive acceptance of these practices as inevitable.

And I don’t blame them. Where would they have learned differently? The technologies and technological policies we impose on students in higher reinforce the digital status quo. Very rarely in our technological practices do we show students that there are in fact alternatives.

This is a point I want to emphasize because I credit my own technological awakening to my exposure to community-governed software as a graduate student. At my institution, a group of academics ran a platform for our community called the The CUNY Academic Commons that enabled anyone at the institution to create public and private websites and groups. Its intent was to foster a more collaborative and publicly-engaged academic community.

And it did. But it also did something else. Unlike Blackboard, Google, and the other proprietary tools we used at CUNY, the developers of the tool were part of our academic community. And their motive was to serve this community, rather than profit, monitor, or control us. There was no Big Other hiding in our midst.

I liked the Commons a great deal but I thought it fell short in enabling students to network their writing with other students. Because the developers were in the building, I had the real possibility of talking over ideas about how the Commons might better support the creation of a student public. Those conversations led to the development of a tool called Social Paper, which was designed to network writing for students that were eager to broaden their writing communities.

I don’t have time to talk much about Social Paper now, but I want to emphasize the point that exposure to community-driven software completely transformed my imagination about who could participate in shaping technology and what sort of interests it could serve. Had we been using Google instead of community-drive software, I would have never bothered to imagine how the tool might be different, or how the tools we use in the academy have profound influence on our knowledge making activities and communities.

That experience has left me with an ongoing pipe dream to allow students to develop and govern their educational technology, to allow them to shape technology according to their needs and values, rather than the values of Big Other. What would it look like if we handed over some portion of the billions of dollars higher education spends on technology to enable them to imagine and build Big Us? Just like student newspapers, there would be a real educational, social, and political value in giving students ownership over the platforms that mediate their intellectual production and communities.

That’s my pipe dream or the image that guides many of the different projects that I do in academic technology. I’m sharing it, though, not because I know it to be a perfect answer but because I hope we can all begin to imagine ways we might transform technology and technological practice in the academy that better serve democracy, equity, freedom, and wellbeing. And this work, I want to stress, need not even be technological in itself. Our disciplinary bodies of knowledge, in fact, have much to offer this exercise. For example, how might history, literature, or philosophy help us broaden our imagination about the possibilities of knowledge systems? What kinds of stories, art, heroic figures, and other cultural forms might help us overcome the flow of powerlessness, apathy, and complacency towards surveillance technology and exploitative forms of information technology? How can we work with students and faculty and librarians and IT workers to flood the public imagination with alternative technological visions?

In short, let’s imagine what it will take to make a world where knowledge making systems are designed to empower rather than alienate its makers.

Thank you.

Works cited

Hardt, M. and Negri, A. 2009. Of love possessed. Artforum International, 48(2): 180–264.

Imarisha, Walidah, ed. Octavia’s Brood: science fiction stories from social justice movements. AK Press, 2015.

Russell, David R. Writing in the academic disciplines: A curricular history. SIU Press, 2002.

Streeby, Shelley. Imagining the future of climate change: world-making through science fiction and activism. Vol. 5. Univ of California Press, 2018.

Zuboff, Shoshana. “Big other: surveillance capitalism and the prospects of an information civilization.” Journal of Information Technology 30.1 (2015): 75-89.

—The age of surveillance capitalism: The fight for a human future at the new frontier of power. Profile Books, 2019.