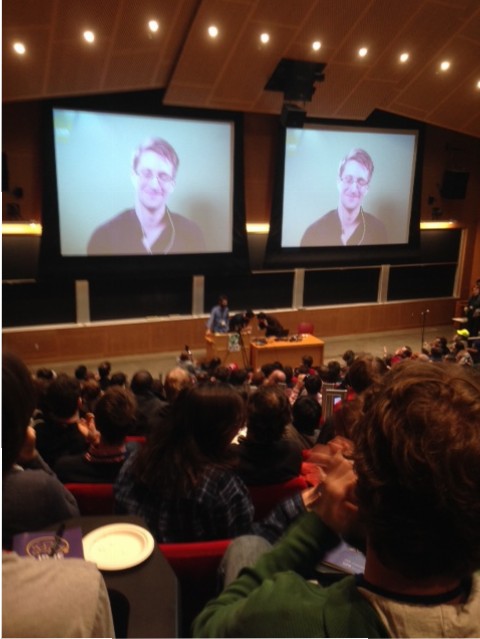

Edward Snowden appearing bashful before his keynote on free software and security at LibrePlanet 2016. Regardless of one’s personal politics however, educators should take note that free software has deep pedagogical application as well.

This post is adopted from a talk I gave with Evan Misshula and Scott Dexter at LibrePlanet 2016, an annual conference hosted by the Free Software Foundation dedicated to issues and activism related to digital freedom. Our collaborative presentation highlighted the critical role that the university plays in reinforcing the dominance of “proprietary” or “nonfree software” in today’s popular market. While Evan and Scott focused on the hazards of proprietary software in areas within the university explicitly devoted to computer science, I focused on the dramatic influence of a research and pedagogy area rarely linked to software politics, that is, the humanities. Here I argue that proprietary software supports a hidden and detrimental assumption within the university about the nature of learning and suggest a collaborative intervention that would enlarge freedom for software culture and the global student body alike.

There are at least two major ways in which the university reinforces the dominance of proprietary software. As Scott mentioned in his talk, and has detailed at great length in his book with Samir Chopra, Decoding Liberation: The Promise of Free and Open Source Software, computer science departments are often immersed within a proprietary culture without adequate recognition of how this inflects their course of study. The implications of this circumstance should be quite shocking even to those with little understanding of the field. Proprietary software, as many of you are already very aware, obscures the code from the user, and thus within the context of education, literally hides both the object and instrument of study from the student. Whatever sort of learning does occur in such a scenario, we must understand it to be a learning that is obedient and whose limits are determined in advance. Anyone interested in the conditions and importance of critical thought should have much to meditate upon here.

But the computer science department is perhaps one of the more obvious places to scrutinize. When I hear the free software community discuss issues related to the university, it is often in regard to departments that explicitly study computer science or develop their own software. And of course, it is critical that we attend to the software politics of the formal site of reproduction of computer science. However, this is not the only site of software use within the university that carries great consequence. For the fact of the matter is that practically speaking every member of the university — regardless of discipline – uses software for almost every aspect of their professional or student activities. And this banal everyday usage arguably strengthens proprietary software’s social and economic grip just as much as a formal blessing from computer science. From word processors to learning management systems, the university relies so deeply on proprietary software that one could hardly imagine the shape of higher education without it. These activities of course are completely outside the activities and influence of the computer science department but they are no less consequential on the reproduction of proprietary software culture at large.

To many FOSS advocates, this may sound like just one more bullet point in the long list of territories colonized by proprietary software. However, I think there is something special about the sphere of higher education especially in regards to its potential to influence broader culture. According to the National Center for Educational Statistics, around 20 million Americans attend some form of higher education a year. The fact that this number translates directly into a software user base has not been lost on the edtech industry which has worked tirelessly to entrench proprietary software within all aspects of higher education. Their success has meant that college not only teaches particular subjects of study, but also apathy and powerlessness with respect to the software systems that shape and monitor user activities. If the FOSS community is looking for ways to grow, it should consider intervening not only via important, grass-roots efforts, but also in higher education, where software consciousness of the masses is produced and disciplined at scale.

How then do we begin to do this? How do we seize this incredible opportunity to immerse 20 million students in participatory, community-oriented software cultures that could potentially reshape the ways they imagine, contribute to, and politicize software for the rest of their lives? We could of course focus on communicating the availability and political import of FOSS to the academic community and hope that one by one they come to engage more consciously with their software. On its own, however, I do not think this approach will be very effective. While the generous educator/administrator/student will perhaps patiently listen to an explanation about Emacs or LibreOffice, they will not understand why it’s worth the technical difficulty or even mild inconvenience when they are already quite content with the tools they have. In short, I do not think we should consider the ethical or technical principles as the sole selling points of FOSS. As much as the FOSS community might pride itself on these principles, I would argue that it is actually the communal joy that these principles make possible which sustains and grows the community.

Nathan Schneider highlights the importance of this communal joy in his article “The Joy of Slow Computing.” I think it’s worth excerpting here as he quite eloquently describes how this joy literally changes his user experience of software. He writes:

…early on, I noticed that the glitches started to feel different than they used to. Stuff that would have driven me crazy on a MacBook didn’t upset me anymore. No longer could I curse some abstract corporation somewhere. As in Slow Food—with its unhygienic soil, disorderly farmers’ markets, and inconvenient seasons—the annoyances of Slow Computing have become pleasures. With community-made software, there’s no one to blame but us, the community. We’re not perfect, but we’re working on it. I gave away my MacBook.

As we concern ourselves with the question of communicating FOSS to new audiences, it’s important to remember the centrality of this communal joy. As Schneider’s observations suggest, community can make technical difficulty feel – and indeed be – meaningful. However, this is not just any community, but one formed in the process of working towards a new political reality. The joy of FOSS, as of Slow Food, is in the creation of a participatory alternative to dominant oppressive consumer industries. It is the feeling and actualization of empowerment through cooperation. But this is an extremely difficult aspect to convey through simple explanation. There is no elevator pitch to communicate the social value of free software. And so, how can we preserve this critical, but oh so perishable, aspect of the FOSS message when communicating with the academic community?

I would like to suggest that we do it through experience rather than words. Concretely, I mean that we should set up a seed FOSS project that would be of everyday use for the everyday student with visible and welcoming onramps for participation in development and governance. Or as Sumana Harihareswara very nicely put in her talk this weekend, we need to set up “tidepools,” that is, “friendly newcomer spaces” that protect users from the free software ocean while preparing them for it. Now, in a moment, I will outline my own vision for this seed project which is already well under way. But in to show you why I think this seed project could be so meaningful for the both FOSS community and the student community, I would like to share how I, an English Ph.D. student with strong suspicion towards digital technology, wound up as a passionate, though somewhat frustrated advocate for FOSS within the university.

Several years ago as a graduate student at The CUNY Graduate Center, I first became aware that a group within our institution developed and maintained a FOSS-supported digital commons — The CUNY Academic Commons — for the entire Graduate Center community. This space was (and still is) used to facilitate digital pedagogy and collaborative research. It also enables students, staff, faculty, and research organizations to easily set up websites and communicate across the community. In a not-entirely coincidental twist of fate, it was in a class that used the Commons where I was also first exposed to the ideas of FOSS. Learning about and discussing the ideas of free software in a space made possible by free software was an intellectually transformative experience. I began to see the dramatic influence of software on academic and student life, especially within areas that distance themselves from technical matters such as the humanities. Even more importantly, I was shocked to realize that proprietary software is an active agent in stifling and segregating the intellectual activities of students. This is not the easiest thing to explain but let me try. Proprietary software in higher education – particularly word processors and learning management systems, the bread and butter of course communications — has always been designed by someone other than the student and implemented for the sole purpose of enabling an instructor to evaluate student work. Whatever ideals you might associate with higher education, at the end of the day, “learning” for the most part is about displaying one’s knowledge – in an essay, an exam, a report — for the sole purpose of a grade. And the software used to carry out that task reinforces that individual, hierarchical, evaluative logic of learning.

Now this logic might seem perfectly reasonable to you and I’m certainly not arguing that it has no value. But I’d like to contrast it with the philosophy of learning inherent in FOSS. If we look at the four freedoms we see that they create a pedagogical culture that values the ability to learn from and teach your neighbor. In short, the four freedoms acknowledge and foster the critical importance and joyful incentive of collaborative learning. One does not study for a “grade” so to speak, but to create and share valuable goods within the community. Proprietary software within education doesn’t only prohibit software collaboration, but stifles collaboration at every level of learning and artificially divorces our understanding of intellectual activity and the software which structures and disciplines it. What if, then, I thought, we made higher education — both its software and its intellectual activities — look a lot more like FOSS? Could the same freedoms which enable and incentivize massive global collaboration among developers also provide a model for forging a global student community that joyfully co-produced both knowledge and its structure of circulation? By implementing FOSS in the university might we make higher education, not just the software of higher education, more participatory, collaborative, and publicly engaged?

This is the hope that drove me — initially a technophobic scholar of literature – to dream up Social Paper, a student-driven collaborative writing platform, and join up with The CUNY Academic Commons, its Director Matthew K. Gold, and my co-founder Jennifer Stoops, to develop it. I’m excited to say that last December we launched a beta version that is now being piloted at The CUNY Graduate Center with the invaluable help of many contributors. I will refrain from going into too much detail about the software itself except to say that it is designed to foster peer collaboration, public scholarship, self-reflection, and most importantly, participatory design in ways that are not possible on other platforms. (You can read my argument for Social Paper on the platform itself here and a proposal for its global potential here.) It has been an incredibly exciting and transformative experience. However, it is also an incredibly precarious endeavor. While we’ve been extremely fortunate in receiving grant funds, and also participation from an incredibly talented and generous group of people within the CUNY community, I can already see how difficult it will be with available resources to achieve the vision of this platform, much less maintain it as a sustainable platform for a broader community. I can see now that growth is often not just an ethical imperative for the FOSS community, but a survival skill for a FOSS project. I can see that we need to be better integrated into the FOSS community so as to draw on its counsel and support if these university FOSS projects are to flourish.

And so, I’m asking the FOSS community to consider the critical importance of everyday software within higher education to its broader mission. I know that I am by no means the first to raise attention to this issue, but I find that there is still no coherent community of FOSS educators nor is there a clearly defined path for the “non-techie” academics and educators to join the FOSS community. We need more tide pools. We need more bridges. We need a movement for free software within higher education. It’s my hope that this plea will help carry that work along.